The History of Our English Bible On This

400th Anniversary of the King James Bible

The Bible In English: From Wycliffe through The King

James Bible

Wycliffe Bible – The First English Bible

by Dr. David L. Brown

First Baptist Church

10550 South Howell Ave.

Oak Creek Wisconsin, 53154

© 1999 & 2011 by David L. Brown, Ph.D.

All rights reserved

Printed booklets or e-booklets available -

Email- PastorDavidLBrown@gmail.com

Introduction

For nearly 2000 years the Bible has remained the most controversial and

contested book of all times. While we, in our modern world, take for

granted the abundance of Bibles and Bible translations, there was a time

when men or women who dared to handle, possess, yes, even read, this

sacred Book that, if they were found out, it would cost them there very

life.

Since the crucifixion of Christ, for whom the Gospel record was set

forth, it can be said that the Bible has become the most blood

stained book in all of history.

Men have fought for it; been burned at the stake for it. Believers have

been (and continue to be) imprisoned, beaten, buried alive and killed,

just for reading it. Others have had their bones disinterred, and for

faith in the Word of God and propagating it have been accursed to

damnation and eternal fire by the Roman Catholic Church.

Bible believing Christians have suffered all this and more for daring

to share the powerful words of the Holy Scriptures to a lost and dying

world.

Through the centuries there have always been those who, for the love of

the lost, desired to share the life changing Gospel Message and yet there

are others who are determined to destroy that message. Yet, for those who

believe, the Light of God’s Word shines through, even in the darkest of

times. (This is an adaptation of the introduction by Chris Pinto in the

documentary A Lamp In The Dark: The Untold Story of the Bible by

www.adullamfilms.com)

This is the story of our English Bible.

John Wycliffe – (about 1320 to December 31, 1384)

The Acts of the Apostles records the birth and spread of the Christian

faith in the first century. At a very early period, likely before the end

of the first, or the beginning of the second century, the books of the New

Testament had been collected into one volume. The New Testament was then

repeatedly hand copied and carried by Christians wherever they went. In

fact, for the first five or six centuries the Bible, and particularly the

New Testament, was translated into various languages. But, the Church of

Rome increasingly usurped the autonomy of the local churches and dominated

the realm of Christendom. With the growth and consolidation of popish

power, the Bible, in the language of the people, declined in importance

while the opinions and judgments of the prelates and priests of Rome

became “the law.”

The Bible went from being available in numerous different languages to

just one language, Latin. Why? It was because “the aim of the Romish

prelacy was no less, than the entire monopoly of all ecclesiastical and

secular rule” (The English Bible – History of the Translation of the

Holy Scriptures Into the English Tongue by H. C. Conant; 1856;

p.15). The Roman Church intended to rule the secular and sacred world. In

order to accomplish that goal, Rome had to consolidate her power. Since

knowledge is the vital element of power, the control of knowledge was

paramount. Knowledge of the Word of God, leads to freedom. Our Lord said,

"ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free." John 8:32.

Therefore, the Bible had to be taken away from the people, if they were to

be controlled. So, “instead of God’s Word, man’s word was set up. Instead

of Christ’s Testament, the pope’s testament, that is, Canon law” was

substituted (The Ecclesiastical History: Containing The Acts and

Monuments…1641 Edition; by John Foxe, Volume 2, Book 7, p.56).

Gradually, access to biblical knowledge (and secular knowledge for that

matter) was withdrawn from the people and wholly held in the greedy,

bloody hands of the Roman Catholic establishment. Slowly but surely the

Bible, in the language of the people, was taken away. The light of the

Word of God was virtually extinguished all over the Roman dominated world,

including Britain. Here is but one example of the distressing state of

biblical knowledge. “In 1353, three or four young Irish priests came over

to England to study divinity; but were obligated to return home because

not a copy of the Bible was to be found at Oxford.” (The English

Bible: History of the Translation of the Holy Scriptures Into The English

Tongue; by H. C. Conant; 1856; p.45). So, how did the Catholic

ecclesiastical establishment view this sad state of affairs? “It has

frequently been made the subject of praise to the papal clergy, that they

alone were the depositaries of learning, at a period when all other

classes of society were sunk into ignorance and barbarism.” (Ibid. p.15)

That is a travesty! If the Roman priesthood would have encouraged and

facilitated the spreading of Bible and secular knowledge it would have

been an age of light! But, instead they hid the light of knowledge within

their cloisters, and history now records this period as “The Dark Ages.”

When the Bible was taken away from the common people, “they lost the

charter of their rights as men.” (Ibid. p.16). As time went on the

people became the mere tools and bond-slaves of the priesthood. They

became “the rabble, the vulgar herd, the mob, to be used or abused without

limits or mercy, for the benefit of their masters.” (Ibid. p.16).

J. C. Ryle characterizes the state of English Christianity this way –

“The three centuries immediately preceding our English Reformation…were

probably the darkest period in the history of English Christianity. It was

a period when the Church of this land was thoroughly, entirely, and

completely Roman Catholic – when the Bishop of Rome was the spiritual head

of the Church – when Romanism reined supreme form the Isle of Wright to

Berwick-on-Tweed, and from the Land’s End to the North Foreland, and

ministers and people were all alike Papists. It is no exaggeration to say

that for these three centuries before the Reformation, Christianity in

England seems to have been buried under a mass of ignorance, superstition,

priestcraft, and immorality. The likeness between the religion of this

period and that of the apostolic age was so small, that if St. Paul had

risen from the dead he would hardly have called it Christianity at all.” (Light

From Old Times of Protestant Facts and Men; by J. C. Ryle; first

published in 1890; p. 22)

It is into this sad state of affairs that God raised up a man named

John Wycliffe, commonly called “the Morning Star of the Reformation.”

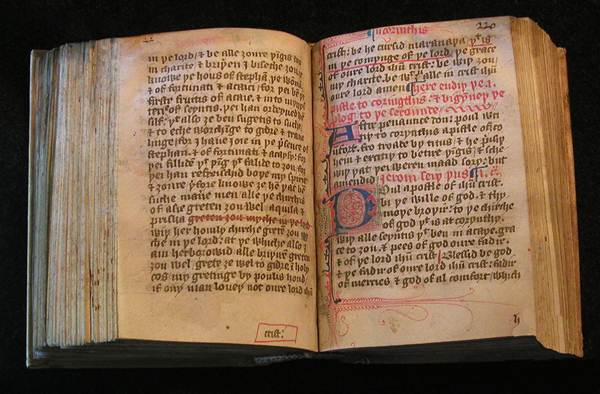

Wycliffe Manuscript New Testament – 1380

Wycliffe Manuscript Old and New Testament – 1382

John Purvy revised Wycliffe’s Bible – 1388

“To Wyclif we owe, more than to any one person who can be mentioned,

our English language, our English Bible, and our reformed religion.”

(Professor Montagu Burrows 1881 lecture series).

He is right. John de Wycliffe was born in the early 1330’s in a

small English village called Wycliffe-on-Tees in Yorkshire, England.

“Roman Catholicism was the religion of the day, and Wycliffe was steeped

in its teachings.” (Zion’s Fire Magazine; March/April, 1991 –

Special Edition; p.8). He was educated at Oxford’s colleges. He began at

Balliol College in 1356 and completed his Bachelor of Arts degree at

Merton College. He received his Doctor of Theology degree in 1372. His

studies, typical of medieval scholars, were rooted soundly in Latin. In

fact, he became a Latin scholar. He also served as Master (head teacher)

of Balliol College and Warden (administrative head) of Canterbury Hall.

How were Wycliffe’s Catholic views changed so drastically that he has

been called “The First Protestant” and “The Morning Star of the

Reformation”? The answer is really very simple. He began to

diligently study the Bible.

“Wycliffe first denounced the corrupt practices and then the

corrupt doctrines of Romanism leading to those practices.” (History

of the Church of God from the Creation to A.D. 1885 by Cushing Biggs

Hassell; p.457). He began preaching, teaching and writing against the

unbiblical doctrines and practices of Roman Catholicism when he was about

35 to 37 years old. Wycliffe exposed the errors of transubstantiation,

sacramentalism, purgatory, indulgences, tradition being equal in authority

with the Scriptures, the papacy, infant baptism, praying to the saints,

and many other false teaching of Roman Catholicism. That is why he is

called the “Morning Star” of the Reformation because he believed, taught,

wrote and preached doctrines that were not advanced until 100 years later

by the Reformers.

By 1371 he was recognized as the leading theologian and philosopher of

the day, second to none in all of Europe. In point of fact, “the splendour

of Wyclif’s talents, learning and character attracted hosts of students,

said to be thirty thousand, who imbibed his opinions. They made him

the hero and idol of the University. He was awarded the honorable title of

‘The Gospel Doctor.’ To the intense chagrin of the ecclesiastics,

he was elected and installed its Professor of Divinity.” (Fighters &

Martyrs for the Freedom of Faith by Luke S. Walmsley; 1912; p.28) In

1372 he began a series of lectures as a part of the divinity course at

Oxford. It was not long before the lecture hall was filled to overflowing.

Many men came to Oxford to sit under his teaching and later followed

him to the Lutterworth parish church. Others like Czech Reformer and

martyr John Hus (martyred July 6, 1415) and Bohemian Reformer and martyr

Jerome of Prague (martyred in 1416) were greatly influenced by Wycliffe’s

writings. “Wycliffe became convinced that everyone had the right and

duty to read the Scriptures in their own language – and that only the

Word of God could break the bondage of Romanism which enslaved the

people.” (Zion’s Fire Magazine; March/April, 1991 – Special

Edition; p.8).

Here are some of the things Wycliffe said about the Bible –

•

The sacred Scripture [is] to be the property of the people, and one which

no party should be allowed to wrest from them.”

•

The priests declare it to be heresy to speak of the Holy Scriptures in

English, such a charge is a condemnation of the Holy Ghost, who first gave

the Scriptures in tongues to the Apostles of Christ, to speak the word in

all languages that were ordained of God under heaven.

•

“Those Heretics who pretend that the laity need not know God’s law but

that the knowledge which priests have had imparted to them by word of

mouth is sufficient, do not deserve to be listened to. For Holy Scriptures

is the faith of the Church, and the more widely its true meaning becomes

known the better it will be. Therefore since the laity should know the

faith, it should be taught in whatever language is most easily

comprehended…Christ and His apostles taught the people in the language

best known to them.”

With the help of his personal secretary, John Purvey, and likely

others, Wycliffe translated the New Testament from Latin into Middle

English in 1380 and the first English manuscript New Testament

appeared. Two years later (1382), again with the help of Nicholas of

Herford and John Purvey the Old Testament was completed and the entire

hand-scribed Bible was issued. The people loved the Wycliffe translation.

For the first time the English people had an opportunity of reading the

Bible in their own language. Up until this time, the Bible had been a

closed book to them. “The arrival of a Bible in the English tongue was not

embraced by all. The English Catholic Church’s opposition to a vernacular

translation was predictable. The authority of the priests rested solely in

the Church. The Church’s grasp on the laity depended on biblical

ignorance. Therefore, they vehemently opposed Wycliffe’s translation.

Any free use of the Bible in worship and thought signaled a deep threat to

the Church’s authority.” (The New Testament in English – Translated

by John Wycliffe – First Exact Facsimile with introduction by Donald L.

Brake; p. xvii)

The English Catholic Church pressured the English Parliament to action.

In 1381 A.D. “the English Parliament passed the first English statute

against heresy, enjoining arrest, trial and imprisonment.” (History of

the Church of God from the Creation to A.D. 1885; by Cushing Biggs

Hassell; p. 459). Soon after this law was enacted Archbishop Courtney

gathered 47 Bishops, monks and religious doctors to examine (try for

heresy) Wycliffe’s teachings in May of 1382. They judged 10 of his

teachings as heresy and 16 others were ruled erroneous and ruled that his

writings were forbidden to be read in England. The King called for the

imprisonment of all who believed the condemned doctrines and teachings of

Wycliffe. When the ruling was made “a powerful earthquake shook the city.

Huge stones fell out of castle walls and pinnacles toppled.” (Rome and

the Bible; by David W. Cloud; Way of Life Literature; p. 57) David

Fountain reports, “Wycliffe called it a judgment of God and afterwards

described the gathering as the Earthquake Council.” (John Wycliffe: The

Dawn of The Reformation; David Guy Fountain; Mayflower Christians

Books; 1984; p. 39)

John Wycliffe was at odds with the Roman Catholic Church nearly all of

his life, but in spite of that he was never excommunicated nor did he

leave the Roman Catholic Church. In fact, he suffered his fatal stroke

while conducting Mass at Lutterworth. He was carried out the door and

taken to his parsonage and died at home in bed on New Year’s Eve 1384 A.D.

He was buried in the Lutterworth church yard soon after. But that was not

the end for John Wycliffe. The English Catholic Church wanted to stamp out

the influence Wycliffe had even after his death. You can see the animosity

by reading what Archbishop Arundel wrote to the Pope in 1411: “This

pestilent and wretched John Wyclif, of cursed memory, that sone of the old

serpant…endeavored by doctrine of Holy Church, devising – to fill up the

measure of his malice – the expedient of a new translation of the

Scriptures into the mother tongue”. (The Wycliffite Versions – The

Cambridge History of the Bible; by Henry Hargreaves; Cambridge

University Press – 1969)

Thirty years after Wycliffe’s death the Roman Church finally took

official action at the Council of Constance in 1415. They burned

Wycliffe’s disciple, John Hus, at the stake and condemned John Wycliffe on

260 different counts. They ordered that his bones be exhumed from the

consecrated ground and burned. Thirteen years after the council, 44 years

after Wycliffe’s death his bones were exhumed and burned along with all

the Bibles and books they could find authored by him. His ashes were

thrown into the river Swift.

The Church of Rome thought this would stamp out his influence and stand

as a warning to any future would-be “heretics”. But, as noted historian

Thomas Fuller put it – “They burnt his bones to ashes and cast them

into the Swift. This brook (Swift) has conveyed his ashes into Avon, Avon

into Severn, Severn into the narrow seas, they into the main ocean. And

thus the ashes of Wycliffe are the emblem of his doctrine, which now is

dispersed all the world over.” (Baptist History: From the

Foundation of the Christian Church to the Present Time; by J. M.

Cramp; Elliot Stock – London; 1871; p.98).

Wycliffe lit the fire that spread Reformation doctrine throughout

Europe.

There

were three major events which made it possible for the Dark Ages to be

shattered by the light of the Bible to shine throughout the European

Continent and then spread to England. First, Johan Gensfleisch zum

Gutenberg invented moveable type to be used with the printing

press. There

were three major events which made it possible for the Dark Ages to be

shattered by the light of the Bible to shine throughout the European

Continent and then spread to England. First, Johan Gensfleisch zum

Gutenberg invented moveable type to be used with the printing

press.

The second event was the downfall of Constantinople to

the Muslims in 1454. The result was that many Greek scholars had to flee

to Europe with their precious manuscripts, including their Greek New

Testament manuscripts. Many of them took positions in the great European

universities and there was a renaissance of ancient learning, including

the teaching of the Greek language. When combined with the invention of

the moveable type printing press, this multiplied the availability of

books.

The third and final event that facilitated releasing the vice

grip grasp of the Roman Church on the world was Erasmus Desiderius

Roterodamus’ collecting New Testament manuscripts and for the first

time ever, publishing all 27 of the New Testament manuscripts in one

book in 1516. In one column is the Greek New Testament text

accompanied by Erasmus’ own new Latin translation, and then this was

followed by Erasmus’ notes, giving his comments on the text. His

translation of the Greek into Latin showed just how corrupt that Latin

Vulgate really was. Between the years 1516 and 1535 Erasmus published five

editions of the Greek New Testament.

It is from Erasmus’ 1522 Greek New Testament that William Tyndale

produced the first printed Bible in English.

The Bibles of the Martyrs

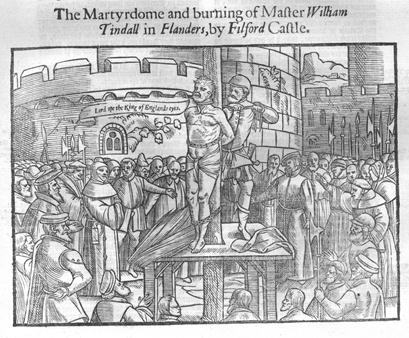

William Tyndale – (1492 – Martyred October 6, 1536)

The Cologne Fragment – 1525

First Edition Tyndale New Testament – 1526

Second Revised & Corrected Tyndale New Testament

Edition – 1534

Tyndale was born sometime in the 1490’s, probably 1492 or 93. The

family sometimes went by the last name Hutchins as well. In 1512 he

entered Oxford. By 1515 he had earned his M.A. He then transferred to

Cambridge University for a time. It is at Cambridge that he likely picked

up his Protestant convictions because the teachings of Luther were

prevalent at Cambridge in the early 1520’s. It should be noted that

Tyndale was a brilliant student. He had mastered seven languages --

Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, French and English. It was said

that he spoke each language so fluently that a person was unable to tell

that it was not his mother tongue. In addition, he had a working knowledge

of German which allowed him to translate and interpret the writings of

Martin Luther. In 1521 he left Cambridge and served through 1523 as

chaplain and tutor in the house of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury. Sir

John was a man of importance and kept “open house for the abbots and

doctors, who were glad for the entertainment and table discussions”.

At one such occasion Tyndale said to a church official “I

defy the Pope and all his laws; if God spares my life, ere many years I

will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scriptures

than thou doest”.

Soon after this encounter Tyndale felt compelled to leave Little

Sodbury Manor. He went to London desiring to try to get ecclesiastical

approval from the Bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstall, to translate the

Bible from Greek into English. It soon became evident that permission

would not be forthcoming. But what Tyndale did get was backing from

Humphrey Manmoth and other merchants to start his translation work. In

1524 Tyndale sailed for Germany, never to see England again. In Hamburg he

worked on the New Testament which was ready to be printed the next year.

He found a printer in Cologne. As the pages of Matthew and Mark (most

likely) began to come off the press Tyndale was warned that a raid had

been planned by Johann Dobneck (alias Cochlaeus). Dobneck was a lead

opponent of the Reformation. Tyndale fled out the back door with the pages

that had been printed, just as the authorities were coming in the front

door. These partial New Testaments were smuggled into England and

distributed. Only one 1525 Gospel portion is known to exist today.

Tyndale moved to Worms to continue his printing. It was a more

reformed-minded city. In 1526 he printed 3,000 (some say 6,000) of these

complete New Testaments. And yet, only two complete Bibles survived and

one partial copy owned by St. Paul’s. The second complete copy was just

discovered in November of 1996 in Stuttgart, Germany. One reason so few

survived was because Bishop Tunstall made arrangements to buy all of them

he could get his hands on. He paid top dollar. In 1526 he preached against

the translation and had great numbers of them ceremoniously burned at St.

Paul’s Cross in London.

Tyndale moved to Antwerp, Belgium around 1527 and published several

books. In 1530 he published the Pentateuch. In 1531 he published Jonah in

pamphlet form. Between 1530 and 1535 he translated Joshua to 2 Chronicles,

but they were not published until after his death. Finally, in 1534

Tyndale published his revised edition and they were smuggled into England.

By 1535 orders had been given to hunt down Tyndale and stop him.

Several Englishmen were about that task. It was the devious Henry Phillips

who found Tyndale and set the trap. On about May 21, 1535 two soldiers

seized Tyndale as he left the home of Thomas Poyntz, Tyndale’s friend. He

was imprisoned in the dungeon of the Castle of Vilvoorde which was located

six miles north of Brussels, Belgium. There he was kept for 18

months until everything was set for his trial. A long list of charges

had been drawn up against him. Here are just of few of the “heresies” he

was charged with:

1. He maintained that faith alone justifies.

2. He maintained that to believe in the forgiveness of sins, and to

embrace the mercy offered in the gospel, was enough for salvation.

3. He denied that there is any purgatory.

4. He affirmed that neither the Virgin nor the Saints pray for us in

their own person.

5. He asserted that neither the Virgin nor the Saints should be invoked

by us.

Tyndale was condemned as an heretic early in August, 1536. A few days

later, with great pageantry and pomp he was cast out of the Church,

defrocked from the priesthood and turned over to the state for punishment.

For some strange reason he was returned to Vilvoorde Castle for another

two months. Finally, early on the morning of October 6, 1536 Tyndale was

led to the stake. His feet were bound tightly to the stake. He was chained

at the waist. A noose of hemp was threaded through the stake and placed

around Tyndale’s neck. The crowd grew silent. Then, with a loud voice

Tyndale prayed, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” The

executioner then snapped down on the noose and strangled him and then he

was burned to ashes.

It should be noted that God did answer Tyndale’s prayer for within a

year afterwards; a Bible was placed in every parish church by the King’s

command.

Myles Coverdale (1488-1569)

1535 – Coverdale Bible: The First Complete

Printed English Bible

1537 – Coverdale Revised Edition

Myles Coverdale was born in 1488 probably in “the district of Coverdale

in Richmondshire, from which district it is probable that his family took

their name”. He received his education in the Priory of the Augustines at

Cambridge, of which the celebrated Dr. Barnes was the head.

John Bale (1548) said of Coverdale: “Under the mastership of Robert

Barnes he drank in good learning with a burning thirst. He was a young man

of a friendly and upright nature and a very gentle spirit. He was one of

the first to make a pure profession of Christ…[and] he gave himself wholly

to the propagating of the truth of Jesus Christ’s gospel…”

On three occasions Coverdale had to flee from England because of his

Reformation views. On the first occasion when he left England during the

latter part of the reign of Henry VIII he became acquainted with Tyndale

and assisted him in his translation work. During that absence he began

working on his own translation of the Bible. Like Wycliffe’s, Coverdale’s

version was a translation of a translation. He “translated from St.

Jerome’s fourth-century Latin version, known as the Vulgate.” He also used

Luther’s German Bible and took much of his English phraseology from

Wycliffe and Tyndale.

Coverdale was not so much a translator as a careful editor and

compiler. He knew how to select, modify and use the materials which were

at hand, so as to produce a Bible which would satisfy the people and the

Ecclesiastics. Hence, while William Tyndale was in the Belgian prison, a

year before his execution, a Bible containing both Old and New Testaments

was printed either in Zurich or at Antwerp, bearing the date October 4,

1535, suddenly appeared in England. It was the Coverdale Bible. It

contained notes, but little, if any, contentious matter. In the

introduction Coverdale declared that he “had not changed so much as one

word for the benefit of any sect, but had with a clear conscience purely

and faithfully translated out of the foregoing interpreters, having only

before his eyes the manifest truth of Scripture.” Two things are to be

noted about this Bible. It was the first edition of the entire

Bible that was printed in English. Secondly, Coverdale’s English

translation was in one column and the Erasmus Latin translation was in the

other.

The 2nd Edition (1537) was published “with the King’s

most gracious license” and therefore was actually the answer to

William Tyndale’s last prayer, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes"

that had been uttered a year earlier.

Coverdale did not have the learning and the resourcefulness of Tyndale

and he knew it; however, he saw the opportunity and the need and put forth

his best effort. He was a noble man. Though he was not martyred, three

times he had to flee for his life. Three times they confiscated everything

he owned. Three times he gave up everything he had for the Bible and the

Testimony of Jesus Christ. He died in February of 1569 and was buried in

St. Bartholomew’s Church.

John Rogers (Born in 1500 -- Martyred February 4, 1555)

1537 - First Edition of Matthews Bible

1549 - A Reprint and a Revision

1551 – Four Editions Were Printed

John Rogers was born about 1500 and martyred in 1555. He

received his B.A. degree at Cambridge in 1525. From there he entered the

priesthood and went to Christ Church, then called Cardinal College in

Oxford, England. About 1534 he became chaplain to the Merchant

Adventurers at Antwerp. There he met William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale.

These two men witnessed to him and as a result he came to a saving

knowledge of Jesus Christ. John Foxe writes of his conversion – “In

conferring with them the Scriptures, he came to great knowledge in the

Gospel of God, insomuch that he cast off the heavy yoke of popery,

perceiving it to be impure and filthy idolatry….”

John Rogers is the preacher responsible for the so-called Matthews

Bible. Before Tyndale was martyred, he appointed Rogers as his literary

executor and left him his unfinished manuscripts covering Joshua to 2

Chronicles.

Rogers desired a version which would contain all the work his friend

Tyndale translated from the original languages because he knew that

Coverdale was not familiar with the original languages of the Bible.

Therefore the Matthews Bible was a composite of Tyndale’s translation from

Genesis to 2 Chronicles, Coverdale’s from Ezra to Malachi and Tyndale’s

New Testament. The Bible would be more accurately called the

Tyndale-Coverdale Bible, yet Rogers knew that he dare not identify this

Bible with Tyndale or it would be rejected. Yet he did not want to

identify it with himself because he was merely the editor and had not done

the translation work. For that reason the pseudonym Thomas Matthew was

used.

1537 Matthews Bible with the huge initials WT

It was probably printed in Antwerp and sent to England to be completed

by Grafton and Whitechurch, London printers. Grafton passed it to Cranmer

who passed it to Cromwell, who gave it to the King and within ten days the

King authorized the sale and reading of the Matthews Bible within his

realm. That is remarkable when you realize that the King despised Tyndale

and just eleven years before, Tyndale’s New Testament was publicly burned!

Yet the Matthews Bible, which he licensed for sale and reading, was

clearly two-thirds Tyndale’s work.

It should be noted that this Bible edition includes introductions,

summaries of chapters as well as some very controversial marginal notes.

Perhaps the most controversial was the note associated with I Peter 3:7.

The note reads –

“He dwelleth with his wyth according to knowledge, that taketh her as a

necessarye healper, and not as a bonde seruaunte or bonde slaue. And yf

she be not obedient and healpfull vnto hym endeueureth to beate the feare

of God into her heade, that therby she maye be compelled to learne her

dutie, and to do it.”

John Rogers was a strong, uncompromising Bible preacher. Historian John

Foxe says when “Bloody” Mary came to power “she banished the true

religion, and restored the superstitions of idolatry of the Church of

Rome, with all the horrid cruelties of blood-thirsty Antichrist”. John

Rogers refused to compromise the Gospel and in fact preached it as

strongly as ever at Saint Paul’s Cross outside the cathedral church of St.

Paul’s in London. For that he was arrested and put in prison and on

February 4, 1555 he was burned at Smithfield.

The Great Bible

1539 – First Edition Great Bible

1540 – Cranmer Edition was appointed

to be read in the churches

1569 – Marks the last of over 30 editions

of The Great Bible

This Bible is also known as Cranmer’s, Cromwell’s, Whitechurch’s or the

Chained Bible. It is called the “Great Bible because it was the largest of

all the English Bibles printed to that time.

Two English Bibles, Coverdale’s and Matthews’, are now being sold with

the authorization of the King. There had been no further decree, however

Coverdale’s Bible was inaccurate in places and was not translated from the

originals, and Matthew’s Bible, the joint Tyndale-Coverdale Bible might

cause trouble for its promoters, if the shrewd Bishop Gardiner and his

friends should succeed in unmasking John Rogers and the Matthew Bible.

Cromwell saw these deficiencies and dangers and he again appealed to

Coverdale to prepare another Bible. It must contain no notes.

The collator and translator of the Great Bible was Myles Coverdale. The

Bible is based upon the Matthew’s Bible and revised to bring it into

conformity with the Hebrew and Latin text of the Complutensian Polyglot.

England was not yet equipped for such beautiful and extensive work as

was desired and permission from the French King (Francis) was secured for

the printing to be done in Paris, by the famous printer Regnault.

Coverdale and Grafton went over to supervise the work. However, the

inquisition was on and it was feared that the work might be stopped.

Bishop Bonner was Ambassador at Paris and as such, might travel without

having his baggage inspected and thus the finished sheets of the printing

went to Cromwell via Bonner. Shortly after an order for confiscation came

from the Inquisitor-General, and the printer was arrested. There was a

delay in the execution and “four great dry vats” of printed matter

were sold as waste paper instead of being burned. Cromwell, by shrewd

management, bought from Regnault the type, presses and other outfit, and

transferred them, along with the printer, to England. The First Edition of

this wonderful specimen of the art of printing was ready for distribution

in 1539.

How The Chapter and Verse Divisions Came To Be In Our English

Bible

The chapter divisions that we use in our Bibles follow the scheme

developed by Stephen Langton who was the Archbishop of Canterbury between

1207 and 1228 AD. As for the verse division, we owe them to Robert

Stephanus (Latin name) also known as Robert Estienne (French). He was a

Paris printer who printed the Erasmus Greek New Testament (Latin as well).

He printed four Greek editions in 1546, 1549, 1550, and 1551. His printing

of these Greek New Testaments aroused the opposition of the Roman Catholic

Church to such an extent that he was forced to leave Paris and flee to

Lyons. He put his family in the carriage, but he rode on horseback. To

occupy his time he took out one of the small 1549 Greek New Testaments he

printed and marked the place the verse divisions were to be made and

numbered them accordingly.

The verse divisions that we use today are because of the efforts of

Stephanus. They first appeared in his Greek-Latin New Testament of 1551

and then a whole Latin Bible in 1555, before they appeared in the 1557

Geneva New Testament and the 1560 Geneva Bible.

The Geneva Bible

1557 – The New Testament

1560 – The Whole Bible

From 1560 to 1644 there were at least 160 Editions

Mary I, the daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, took the

throne in England in 1553 and set the stage for the creation of the Geneva

Bible. Sixteen years earlier her father, Henry VIII, had released the

first Bible in English following his separation from the Catholic Church

at Rome. However, once Mary was in power, she immediately began forcing

all of England back under the authority of the Roman Church and

suppressing the circulation of the Bible in the common (English) tongue.

Specifically, Mary I issued proclamations in August 1553 forbidding

public reading of the Bible and in June 1555 prohibiting the works of

reformers Tyndale, Rogers, Coverdale, Cranmer, and others. In 1558 a

proclamation was issued requiring the delivery of the reformers writings

under penalty of death. A vicious persecution was instituted against

anyone who supported the reformers views or attempted to circulate the

scripture in English. Overall, nearly three hundred people were burned at

the stake under “Bloody” Mary’s reign, and many more were imprisoned,

tortured, or otherwise punished. Reformer John Rogers, who produced the

Matthews Bible, was the first to be burned. Others who followed the same

fate included Bishop Thomas Cranmer, who was involved with the second and

subsequent editions of the Great Bible, Nicolas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, and

John Hooper, who was often referred to as the "Father of Puritanism."

It is estimated that during Bloody Mary’s reign as many as eight

hundred reformers fled England to seek shelter on the Continent. Some

settled in Strasburg, some in Zurich, and some in Frankfort. Many settled

in Geneva, the “Holy City of the Alps,” where Protestantism was supreme.

The city was under the control of the famed scholar, John Calvin, with the

assistance of Theodore Beza. By 1556 a sizeable English-speaking

congregation had formed in Geneva with Scottish reformer John Knox serving

as pastor. William Whittingham, a tremendous scholar who according to

tradition married a sister of Calvin’s wife, succeeded Knox as pastor in

1557.

No new English Bible translations had emerged since the first Great

Bible of 1539, and William Whittingham undertook the work of improving the

English versions of the New Testament. First published in Geneva by Conrad

Badius in 1557, Whittingham produced a revision of William Tyndale’s New

Testament “with most profitable annotations of all hard places.” This

small, thick octavo edition included an epistle by Calvin himself, which

helped to introduce Protestant views to the English people. In this

epistle Calvin declared, “Christ is the End of the Law.”

Immediately after the release of Whittingham’s 1557 New Testament, the

English exiles entered upon a revision of the whole Bible. Assisted by

Beza and possibly Calvin himself, several English exiles were involved in

the translating, but it is impossible to say how many. Myles Coverdale,

who produced the Coverdale and Great Bibles, resided in Geneva for a time

and may have assisted, and a similar claim may be advanced in favor of

John Knox. The famed sixteenth-century English historian, John Foxe, was

also in refuge in Switzerland during this time. Yet the chief credit

belongs to William Whittingham, who was probably assisted by Thomas

Sampson, Anthony Gilby, and possibly William Cole, William Kethe, John

Baron, John Pullain, and John Bodley.

The Old Testament from Genesis through 2 Chronicles and the New

Testament were merely revisions of Tyndale’s previous monumental efforts.

The works of Coverdale, Rogers, and Cranmer were also consulted, and the

English exiles completed a careful collation of Hebrew and Greek

originals. They compared Latin versions, especially Bezas, and the

standard French and German versions as well.

While Coverdale’s, Matthews, and the Great Bible were merely revisions

of Tyndale’s translations from the original Hebrew and Greek, the Geneva

Bible charted new ground. The scholarly English refugees in Geneva

completed the translation of the remainder of the Old Testament directly

from Hebrew into English for the first time. Tyndale had only translated

the Hebrew (Masoretic) text up to 2 Chronicles before he was imprisoned in

1535, and it was not until this handful of scholars assembled in refuge in

Geneva that there was sufficient familiarity with Hebrew among reformers

to complete the translation of the Old Testament directly from Hebrew.

Thus, the English scholars who escaped persecution in their native land

and resided in Geneva produced the first English Bible ever completely

translated from the original languages.

The work took over two years, and in 1560 the world witnessed a new

Bible in English, which is now known as the “Geneva Bible.” In a simple

prefatory note, the Geneva Bible was dedicated to “Bloody” Mary’s

successor, Queen Elizabeth I, the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Bolyen.

The Geneva Bible is a Bible of First’s -

•

It was the 1st and only Bible published during the reign of Mary I

(Bloody Mary).

•

It was the 1st English Bible to be completely translated from the Biblical

languages.

•

It was the 1st Study Bible.

•

It was the 1st Bible to use the easier to read Roman type style instead of

the Black Letter style.

•

It was the 1st English Bible to have verse divisions.

•

It was the 1st English Bible to use italicized words where English

required more than a literal Greek or Hebrew rendering.

The Geneva Bible was used by many well known people. It was…

•

The Bible of Bunyan

•

The Bible of Shakespeare

•

The Bible of Jamestown & Pocahontas

•

The Bible of the Pilgrims

It is called the “Breeches Bible” because of Genesis 3:7 where they

chose the name “breeches” for the covering of Adam and Eve.

The Bishops Bible

1568 First Edition

1572 Revised Edition

The widespread popularity of the Geneva Bible was undermining the

authority of the Great Bible, and also the power of the Bishops.

Puritanism influenced by the reformers on the European Continent was

springing up; non-conformity was in the air. Archbishop Parker and the

Bishops felt that something should be done in Bible translations. In 1564

a revision committee containing eight or nine bishops was formed.

The plan was to follow the Great Bible, except where it varied from the

Hebrew and Greek and to attend to the Latin versions of Munster (often

inaccurate) and Pagmnus, as well as to avoid bitter notes. There were also

numerous tables, calendars, maps and other helps.

The Bishop’s Bible was not popular. Queen Elizabeth took no public

notice of it, nor did she ever give it her formal sanction and authority.

The translation was stiff, formal and difficult. It was unpopular with the

people and could not displace the Geneva Bible. The whole work is

described as “the most unsatisfactory and useless of all the old

translations”. For forty years it was held in ecclesiastical esteem

and twenty editions were issued, the last being in 1606.

1611 -- THE KING JAMES BIBLE (Also known as the

Authorized Version)

Published Continuously for 400 years

According to Vanderbilt University Press, the King James Bible is

the best selling book of all times (Translating for King James

by Allen Ward; Vanderbilt Press, 1969; back cover – by way of Majestic

Legacy compiled by Dr. Phil Stringer; published by The Bible Nation

Society, 2011; p. 7). “More than five billion copies of the King James

Bible have been sold over the last 399 years.” (Majestic Legacy

compiled by Dr. Phil Stringer; published by The Bible Nation Society,

2011; p. 7)

“The King James Version is the crown jewel of English literature.”

(A Visual History of the English Bible; Donald L. Brake; Baker

Books 2008; p. 224) “The King James Bible is the most frequently quoted

document in existence.” (History Channel Magazine – An

advertisement by Thomas Nelson Publishers for KJV400 Celebration).

In fact, the King James Bible is “the most influential book in the history

of English civilization.” (Compton’s Encyclopedia; 1995 Edition, by

way of Phil Stringer’s book).

How The King James Bible Came To Be

James

Stuart (1566-1625) was born to Mary Queen of Scots (Mary I or Mary Stuart)

and her second husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley at Edinburgh Castle. He

was baptized Catholic because of his mother’s faith. It was a turbulent

time in Scotland, the Presbyterians prevailing over Catholics for

religious domination. He ascended the throne of Scotland in July 1567, at

age 13 months, when his Roman Catholic mother Mary Queen of Scots

(1542-1587) was forced to abdicate. His mother Mary left the kingdom on

May 16, 1568, and never saw her son again. James

Stuart (1566-1625) was born to Mary Queen of Scots (Mary I or Mary Stuart)

and her second husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley at Edinburgh Castle. He

was baptized Catholic because of his mother’s faith. It was a turbulent

time in Scotland, the Presbyterians prevailing over Catholics for

religious domination. He ascended the throne of Scotland in July 1567, at

age 13 months, when his Roman Catholic mother Mary Queen of Scots

(1542-1587) was forced to abdicate. His mother Mary left the kingdom on

May 16, 1568, and never saw her son again.

The reason Mary was forced to abdicate was James’s father, Henry

Stuart, was murdered in mysterious circumstances shortly after James was

born. He was assassinated and it was rumored that Mary had a part in the

crime. There had developed a rift between Mary and Henry that became

public knowledge. For help, Mary turned to a Scottish nobleman, a very

powerful man, the Earl of Bothwell. He engaged the help of other Scottish

noblemen to do whatever they could to help the queen in her dilemma. This

led to a failed explosion plot and to the strangulation death of Henry

Lord Darnley. A few months later, Mary and the Earl married. This incensed

the populace who suspected Lord Bothwell’s participation in the murder of

their King. Her outraged subjects turned against her.

In July of 1567, at the age of 13 months, James ascended to the throne

as King James the VI of Scotland. Though baptized Catholic, he was brought

up under the influence of reformed Scottish Protestants. His tutor was the

historian and poet George Buchanan who was a positive influence on him.

James proved to be a capable scholar.

A succession of regents ruled Scotland until 1576,

when James became nominal ruler, although he did not actually take control

until 1581. He proved to be an astute ruler who effectively controlled the

various religious and political factions in Scotland.

In 1586, James and Elizabeth I became allies under

the Treaty of Berwick. When his mother, Mary Stuart, was executed by

Elizabeth the following year, James did not protest too loudly because he

hoped to be named as Elizabeth's successor.

Some wonder why Mary was executed. Here is why.

Mary fled to England when she abdicated, seeking

the protection of her first cousin once removed, Queen Elizabeth I of

England. She hoped to inherit her kingdom. Mary had previously claimed

Elizabeth's throne as her own and was considered the legitimate sovereign

of England by many English Catholics, including participants in the Rising

of the North in 1569, the unsuccessful attempt by the Catholic Nobles of

Northern England to depose Elizabeth and make Mary Stuart Queen.

Perceiving her as a threat, Elizabeth had her arrested. After 19 years in

custody in a number of castles and manor houses in England, the

44-year-old former queen was tried for treason on charges that she was

involved in three plots to assassinate Elizabeth and found guilty. She was

beheaded at Fortheringhay Castle in 1587. Interestingly enough, in 1612

James moved his mother‘s body to Westminster Abbey, constructing for her a

magnificent tomb that rivaled that of Elizabeth.

In 1589, James married Anne of Denmark. They

had eight children, of whom only three lived beyond infancy: Henry, Prince

of Wales (1594-1612), Elizabeth Stuart (1596-1662), and Charles, who

became king upon James’ death (1600-1649).

In March 1603, Elizabeth died and James VI of

Scotland became King James I of England and Ireland in a remarkably smooth

transition of power. After 1603 he only visited Scotland once, in 1617.

James was known as the most educated sovereign in Europe. While he had

some good qualities, he was not very popular. Catholics hatched a plot to

kill him and others on November 5, 1605, in the Gun Powder Plot.

Guy Fawkes was caught in the act of attempting to carry out the deed.

The Division In The Church of England

When James came to the throne all was not well in the Church of

England. There were three Protestant versions of the English Bible in

circulation:

1) The

Great Bible of 1539 still was used in the Church of England in its Psalm

readings.

2) The

Geneva Bible of 1560 was loved by the people because of the verse

divisions and the commentary.

3) The

Bishops' Bible of 1568 was the official Bible of the Church but the

translation was stiff, formal and difficult. It has been described as

“the most unsatisfactory and useless of all the old translations.”

Likewise, the Church of England was very divided. There were 3

factions. The Romanists wanted to return to the Roman Catholic Church. The

Low Church or Puritan party wanted to “purify” the church of

Catholicism and maintain an evangelical stance in the church. The

Anglo-Catholics or High party was the ritualistic group who wanted an

independent English church but keep many of the Roman Catholic rituals,

doctrines and traditions. King James did not agree with any of these

groups.

The Puritan party complained of certain grievances they had with church

officials. James had been proclaimed King on the 24th of March

in 1603. It was not until the May 7th that he entered London to

take possession of the throne. “Between these two dates, and while he was

the guest of the Cromwell’s of Hinchinbrook, near Huntingdon, he was

approached by certain of the puritan clergy who presented him with what is

known as the Millenary Petition.”

It was claimed by the circulators of the petition that 1,000 Puritan

ministers hand signed the petition.

The Puritans objected to the priest's making the sign of the cross

during Baptism; the use of the ring for marriage which had no

biblical basis; the rite of confirmation; Ministers' wearing of

surplices (robes). They viewed them as too Catholic, unessential and

extra-biblical, if not completely unbiblical.

King James I wanted to bring unity within the Anglican Church,

therefore he called a conference to be held at Hampton Court Palace on

January 16th, 1604, at which representatives of both parties

were to have an opportunity of stating their views to His Majesty.

“The Hampton Court was built by Cardinal Woolsley in 1515 and it

pictures the excesses of the age in which it was built. It took 2500

workmen to build its 1000 rooms.” (Comment by Dr. Ken Connolly in his

video – The Story of The English Bible). It took 500 servants or

paid employees to keep it. “It happens to have 250 tons of lead pipe that

brings special water into it because they would not use the water which

came from the River Thames.” (Ibid.) Hampton Court aptly illustrates the

decadence of the prelates of the church. Remember, the man that built it

was the ecclesiastical head of the Church in England in his day.

I find it ironic that on Monday, January 6, 1604 James I called about

50 prelates (high ranking church officials) of the church together in an

effort to try to straighten out some problems the two factions were

having. On the second day of the proceedings, the Puritan President of

Corpus Christi College in Oxford, Dr. John Rainolds “moved His Majesty

that there might be a new translation of the Bible, because those which

were allowed in the reign of Henry VIII, and Edward VI were corrupt and

not answerable to the truth of the original.”

The King, sympathetic to the idea, exerted his royal influence to

advance the project. King James said he “wished that some special

pains should be taken in that behalf for one uniform translation

(professing that he could never yet see a Bible well translated in

English, but the worse of all his Majesty through the Geneva to be), and

this to be done by the best learned in both Universities; after them to be

reviewed by the bishops and the chief learned of the Church; from them to

be presented to the Privy Council; and lastly, to be ratified by his royal

authority…He gave this caveat (upon a word cast out by my Lord of London)

that no marginal notes should be added, having found in them, which are

annexed to the Geneva translation, some notes very partial, untrue,

seditious, and savouring too much of dangerous and traitorous conceits.”

(The Printed English Bible by Richard Lovett; pp.134-135)

The Translation

The next step was the actual selection of the men who were to do the

translation work. In July of 1604, King James wrote to Bishop Bancroft

that he had “appointed certain learned men, to the number of four and

fifty, for the translating of the Bible.” These men were the best biblical

scholars and linguists of their day. In the preface to their completed

work it is further stated, “there were many chosen, that were

greater in other men's eyes than in their own, and that sought the truth

rather than their own praise. Again, they came or were thought to come to

the work, learned, not to learn." Other men were sought out,

according to James, “so that our said intended translation may have

the help and furtherance of all our principal learned men within this our

kingdom.”

Although fifty-four men were nominated, only forty-seven were known to

have taken part in the work of translation. Historians indicate that a

number of these changes were due to death. It should also be noted, as the

11th Edition of Encyclopedia Britannica says, “It is observable

also that they [the translators] were chosen without reference to party,

at least as many of the Puritan clergy as of the opposite party being

placed on the committees.” (Encyclopedia Britannica – 11th

Edition of 1911; Volume III; p.902)

Bishop Lancelot Andrews, who besides having an intimate knowledge of

Chaldee, Hebrew, Greek, and Syriac, was familiar with 10 other languages,

chaired the translating work. The translating team was divided into 6

divisions; two at Westminster, two at Cambridge, and two

at Oxford.

The translation work did not get underway until 1607. When it did, ten

at Westminster were assigned Genesis through 2 Kings; the

second team of 7 had Romans through Jude.

At Cambridge, eight worked on 1 Chronicles through

Ecclesiastes, while seven others handled the Apocrypha.

Oxford employed seven to translate Isaiah through Malachi;

eight occupied themselves with the Gospels, Acts, and Revelation.

As each group completed their particular assigned part, it was then

subjected to the other 5 sets of men so that each part of the Bible came

from all the learned men. When they had completed their work, a final

committee of six members at London carefully reviewed it.

These Fifteen general rules were advanced for the guidance of

the translators:

·

The ordinary Bible read in the Church, commonly called the Bishops’ Bible,

to be followed, and as little altered as the Truth of the original will

permit.

·

The names of the Prophets, and the Holy Writers, with the other Names of

the Text, to be retained, as nigh as may be, accordingly as they were

vulgarly used.

·

The Old Ecclesiastical Words to be kept, viz. the Word Church not to be

translated Congregation, etc.

·

When a Word hath divers Significations, that to be kept which hath been

most commonly used by the most of the Ancient Fathers, being agreeable to

the Propriety of the Place, and the Analogy of the Faith.

·

The Division of the Chapters to be altered, either not at all, or as

little as may be, if Necessity so require.

·

No Marginal Notes at all to be affixed, but only for the explanation of

the Hebrew or Greek Words, which cannot without some circumlocution, so

briefly and fitly be expressed in the Text.

·

Such Quotations of Places to be marginally set down as shall serve for the

fit Reference of one Scripture to another.

·

Every particular Man of each Company, to take the same Chapter or

Chapters, and having translated or amended them severally by himself,

where he thinketh good, all to meet together, confer what they have done,

and agree for their Parts what shall stand.

·

As any one Company hath dispatched any one Book in this Manner they shall

send it to the rest, to be considered of seriously and judiciously, for

His Majesty is very careful in this Point.

·

If any Company, upon the Review of the Book so sent, doubt or differ upon

any Place, to send them Word thereof; note the Place, and withal send the

Reasons, to which if they consent not, the Difference to be compounded at

the general Meeting, which is to be of the chief Persons of each Company,

at the end of the Work.

·

When any Place of special Obscurity is doubted of, Letters to be directed

by Authority, to send to any Learned Man in the Land, for his Judgment of

such a Place.

·

Letters to be sent from every Bishop to the rest of his Clergy,

admonishing them of this Translation in hand; and to move and charge as

many skilful in the Tongues; and having taken pains in that kind, to send

his particular Observations to the Company, either at Westminster,

Cambridge, or Oxford.

·

The Directors in each Company, to be the Deans of Westminster, and Chester

for that Place; and the King's Professors in the Hebrew or Greek in either

University.

·

These translations to be used when they agree better with the Text than

the Bishops’ Bible: Tyndale's, Matthew's, Coverdale's, Whitchurch's,

Geneva.

·

Besides the said Directors before mentioned, three or four of the most

Ancient and Grave Divines, in either of the Universities, not employed in

Translating, to be assigned by the vice-Chancellor, upon Conference with

the rest of the Heads, to be Overseers of the Translations as well Hebrew

as Greek, for the better observation of the 4th Rule above specified.

“The execution of the work occupied about three years, and both the

length of time employed and the elaborate mode of procedure adopted

indicate the pains that were taken to make the translation worthy of its

high design. In 1611 the new version was given forth to the public.

There seem to have been two impressions of this first edition,

probably due to the impossibility of one printing office being able to

supply in the time allotted the number of copies required, about 20,000.”

(A Brief Sketch of The History of the Transmission of the Bible Down to

the Revised English Version of 1881-1885 by Henry Guppy; 1936).

Before I move on, I want to clarify Guppy’s statement; there seem to

have been two impressions of this first edition. Here is what he is

referring to. There is the so called “she” Bible and the “he”

Bible. The “he” Bible is the rarer of the two. The way to

distinguish between the two is by turning to Ruth 3:15 and if it

reads -- "Also he said, Bring the veil that thou hast upon thee,

and hold it. And when she held it, he measured six measures of

barley, and laid it on her: and she went into the city," it

is a “she” Bible. If, on the other hand, the last part of the verse

reads – “he measured six measures of barley, and laid it on

her: and he went into the city," it is a “he” Bible. All of

the King James Bibles of our time, with the exception of the 1611 Thomas

Nelson reprint, are “she” Bibles. There are those who would point

to this as an error on the part of the translators. I’m not so sure.

Here’s why. There are Hebrew manuscripts that include the same variant.

Therefore, the problem is with the Hebrew as it is confusing.

As I come to the end of this booklet on the King James Version of the

Bible I want to note that in England particularly, it is commonly referred

to as the “Authorized Version.” But strange it was never formally

authorized. To date, no evidence has been produced “to show that the

version was ever publicly sanctioned by Convocation, or by Parliament, or

by the Privy Council, or by the King. It was not even entered at

Stationers' Hall, with the result that it is now impossible to say at what

period of the year 1611 the book was actually published. (Ibid.)

No other translation past or present has been so meticulously done and

carefully reviewed. The superintending hand of God was apparent. As one

author put it, “the result was an edition of the Word of God unrivaled for

its simplicity, for its force, and for its vigor of language. It was, and

is to this day, a compendium of literary excellencies, and much better,

has proved itself to be a faithful and accurate translation of the very

Word of God.”

We can readily discern from the instructions given to the translators

that our King James Bible was “Newly translated out of the original

tongues and with the former translations diligently compared and revised.”

It was, “Printed by His Majesty's special command, and appointed to be

read in the churches.” It is to this day the premier of all English

translations, being a most scholarly, accurate, and faithfully executed

witness of the very mind of God.

King James 1611 First Edition, First Printing

The Great “He” Bible

|